#65 – Do we learn from mistakes? How?

Episode host: Linda Snell.

The growth mindset, which involves learning from mistakes, is a crucial part of professional development for both trainees and seasoned practitioners. This episode explores how experienced clinicians reflect on both their errors and successes to enhance their practice.

Episode 65 transcript. Enjoy PapersPodcast as a versatile learning resource the way you prefer—read, translate, and explore!

Episode article

Kotwal, S., Howell, M., Zwaan, L., & Wright, S. M. (2024). “Exploring Clinical Lessons Learned by Experienced Hospitalists from Diagnostic Errors and Successes”. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 39(8), 1386–1392.

Episode notes

Background

We all make mistakes—but do we truly learn from them? In medicine, mistakes are unfortunately common, particularly diagnostic errors. But what if we could view these errors as opportunities for growth rather than sources of blame? By adopting a growth mindset, clinicians can improve their competence through feedback and reflection on their clinical experiences.

This paper explores the concept of “Safety-I and Safety-II” in medical practice. While Safety-I focuses on identifying the causes of errors to prevent harm, Safety-II emphasizes replicating successes to establish best practices. Hospitalists, who care for many hospitalized patients in the US, play a critical role in diagnosis and management, as well as promoting patient safety. However, the lessons learned by experienced hospitalists from their diagnostic errors and successes have not yet been fully described.

Purpose

To fill this gap, the study aimed to identify and characterize the clinical lessons learned by seasoned hospitalists from both diagnostic errors and successes in patient care. Specifically, the research sought to understand how these clinicians learn from their clinical experiences over time.

Methods

- A qualitative study conducted within an interpretivist (constructivist) framework, which holds reality as multiple and subjective, related to how individuals understand and create their own meanings influenced by specific social contexts.

- Semi-structured interviews were conducted with hospitalists having over five years of experience, across three community and three academic hospitals in the Baltimore/Washington area. Out of 91 eligible participants, 30 invited and 24 hospitalists were interviewed.

- The interview guide focused on participants’ experiences with difficult diagnoses and the lessons learned from both successes and failures.

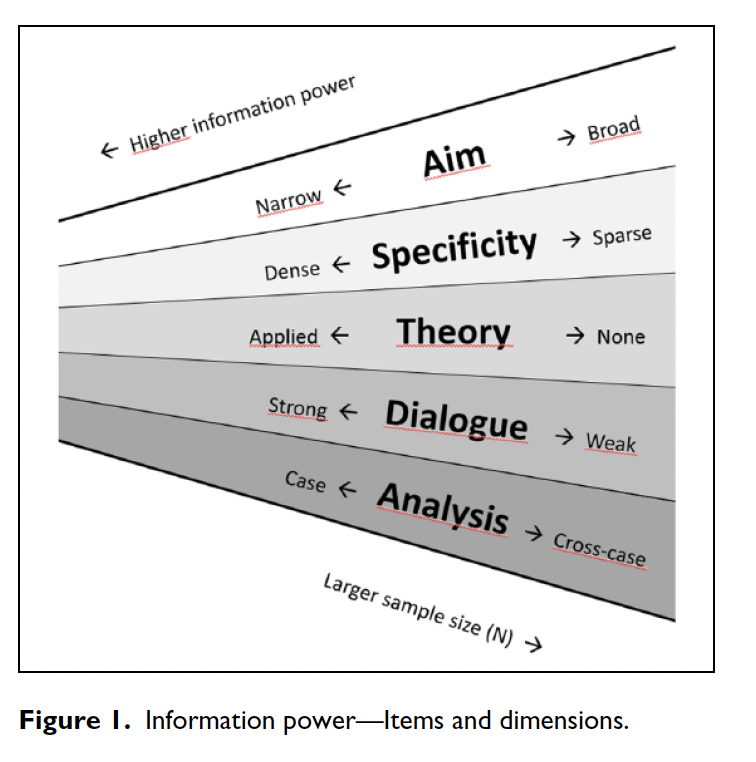

- Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyze the data, with information power ensuring the adequacy of the sample.

Information Power summary

Information Power is a concept from the 2015 paper “Sample Size and Qualitative Interviews” by Malterud et al. It addresses how to determine if you have enough data in qualitative research, where traditional power calculations aren’t applicable. Instead, five factors guide this assessment:

- Study Aim: Broad questions require more data; narrow questions need less.

- Sample Specificity: More specific experiences need smaller samples.

- Established Theory: Using a guiding theory reduces the data needed compared to studies without one.

- Quality of Dialogue: Eloquent participants who articulate well mean fewer interviews are needed.

- Analysis Strategy: Exploring multiple cases requires more participants than exploring a single case, in-depth, using a methodology like narrative analysis.

For a visual representation of these factors, check the page Information Power in Qualitative Interview Studies- The Model (Sage Journals), where you will find the figure in the Malterud paper that Lara refers to.

Results/Findings

The hospitalists represented a broad range of demographics, with a quarter having roles in quality or safety. The study identified five key themes:

- Appreciating Excellence in Clinical Reasoning as a Core Skill: Emphasizing foundational skills like history-taking, physical exams, test utilization, and clinical humility.

- Connecting with Patients and Team Members to Gain Insights: Listening to and respecting both patients and colleagues.

- Reflecting on the Diagnostic Process: Reevaluating assumptions, revisiting unresolved issues, slowing down, and going back to primary data when necessary.

- Committing to Growth: Adopting a growth mindset through follow-ups after handovers and learning outcomes, sometimes with the support of a clinical coach.

- Prioritizing Self-Care: Maintaining well-being through mindfulness and activities outside of medicine to improve clinical performance.

How does this compare to what is known?

The findings align with existing literature on diagnostic education, particularly around clinical reasoning errors. However, this study adds nuance by highlighting specific dimensions of diagnostic excellence, reinforcing the importance of a growth mindset and continuous learning.

Conclusions

The study concludes that experienced hospitalists learn essential lessons from both errors and successes. These findings could serve as a blueprint for creating priorities for continuous learning among clinicians and healthcare organizations.

Paper clips

The authors successfully make a qualitative educational study relevant and digestible for clinicians. My key takeaway? We must continue to teach—and ensure the learning of—fundamental clinical skills, while fostering clinical humility.

Resources mentioned in the episode

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). “Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power”. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760.

Icon by Cattaleeya Thongsriphong on freeicons.io

0 comments