#72 – Is this program competency-based?

Episode host: Jason R. Frank.

In this episode, Jason is tackling a big question in health education: what does it really mean for a program to be “competency-based”? With Competency-Based education (CBE) becoming a global standard in health professions, the episode breaks down what makes a program truly CBE, from focusing on outcomes and skill progression to using tailored learning experiences and programmatic assessments.

Listeners get a clear guide to spotting whether a curriculum is Competency-Based and why this approach is reshaping training to ensure all graduates meet essential standards in their field.

Episode 72 transcript. Enjoy PapersPodcast as a versatile learning resource the way you prefer- read, translate, and explore!

Is your program Competency-Based? A guide for clinician educators

In the evolving landscape of health professions education, “Competency-based Education” (CBE) is now more than just a buzzword. For clinician educators, administrators, and leaders, understanding CBE is crucial for designing programs that ensure every graduate meets the standards necessary for quality patient care. But what exactly is Competency-Based Education, and how can you tell if a program truly embodies it? Let’s explore the core principles of CBE and offer a framework for identifying Competency-Based programs.

What is Competency-Based Education (CBE)?

Competency-Based Education is an approach to curriculum design that prioritizes defined outcomes—specifically, the competencies students must achieve before they graduate. While traditional programs might rely on time-based structures or apprenticeship-style learning, CBE reshapes the educational model to emphasize specific skills and knowledge that graduates must demonstrate. In CBE, time is a resource rather than a benchmark; the focus is on a learner’s progress and mastery of essential skills.

Competency-based models originated in broader educational fields as early as the 1910s, but in health professions, CBE gained traction following a 1978 World Health Organization (WHO) report by McGahey and colleagues. Their findings highlighted the variability in health professions training worldwide, suggesting that programs should focus less on time and more on ensuring graduates acquire the necessary abilities. Since then, CBE has become a foundation for health professions education worldwide.

Why Competency-Based Education? The Drivers Behind CBE

Traditional education models have long relied on apprenticeship systems, where students are immersed in practice under experienced clinicians until deemed competent. But this time-based model has significant drawbacks, such as variability in graduate competence, which can sometimes lead to gaps in abilities and, ultimately, to patient harm.

The movement toward CBE aims to eliminate these discrepancies by ensuring that all graduates meet minimum standards. However, CBE is not merely about meeting the minimum requirements. It supports a learner-centred approach that prioritizes mastery, aiming to graduate clinicians who are not only minimally competent but also prepared to excel.

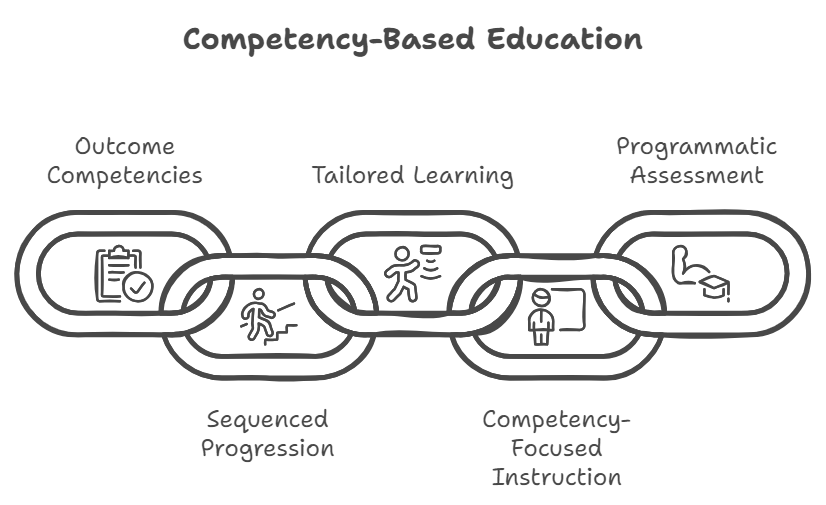

The Five Core components of Competency-Based Education

Elaine Van Melle and colleagues outlined five essential components of CBE, which provide a reliable framework for evaluating whether a program is truly competency-based. Here’s a breakdown of these components and how each contributes to effective program design.

- Outcomes competencies defined

The first step in any CBE program is identifying the competencies graduates need. This requires a systematic needs assessment to determine the abilities essential for practice. Health professions programs may use job task analyses, social accountability mandates, and patient needs assessments to define these competencies. In CBE, competencies aren’t just technical skills; they also address the societal and contextual needs of the healthcare system. - Sequenced progression of competency acquisition

CBE emphasizes a progressive learning pathway that begins with foundational skills and culminates in higher levels of expertise. Unlike traditional models where time in training dictates progression, CBE models sequence learning activities deliberately to match a learner’s evolving level of expertise. For example, a resident in emergency medicine starts as a novice, gradually taking on more responsibility until they are ready to function as a junior colleague or “junior attending.” - Tailored learning experiences

Tailoring learning experiences means designing a curriculum where specific activities are mapped to competencies. In traditional models, students often rotate through clinical settings based on a predetermined schedule. In contrast, CBE programs deliberately select and structure experiences so learners acquire required competencies effectively. Blueprinting and mapping help educators ensure that each learner gains the necessary experiences to meet all outcomes. - Competency-Focused Instruction

In CBE, instruction is purposefully aligned with defined competencies. Teachers diagnose each learner’s level and tailor their teaching interventions accordingly. Competency-focused instruction requires teachers to be aware of the curriculum’s blueprint and to direct their efforts toward closing any skill gaps in learners. In essence, teaching in CBE goes beyond delivering content—it’s about fostering progression through targeted support. - Programmatic assessment

Unlike traditional high-stakes exams or retrospective assessments, CBE embraces a model of programmatic assessment. This involves a variety of low-stakes assessments gathered over time, providing a holistic view of a learner’s progress. Programmatic assessment relies on multiple observations in authentic clinical settings, allowing educators to assemble a reliable picture of the learner’s competence. CBE’s programmatic assessment often culminates in competency committees, which review each learner’s performance and make systematic decisions about their readiness for independent practice.

How does a Competency-Based Program look in practice?

Programs that follow CBE principles might look familiar on the surface, but a closer look reveals distinct features:

- Competency-Based teaching: Educators use principles of mastery learning, focusing on defined competencies and providing feedback to guide learners’ progress. Teaching is highly intentional and aligns with the program’s competency framework.

- Competency-Based assessment: Assessments are both “of learning” and “for learning,” emphasizing frequent, low-stakes observations. Data from these assessments is used to guide learners in real time, providing coaching opportunities and meaningful feedback that support their growth.

- Curriculum blueprinting: Competency-based programs use blueprints that map experiences to required competencies. Teachers and administrators alike understand how each learning activity contributes to the program’s goals, ensuring that the curriculum is both intentional and comprehensive.

Implementing CBE in Health Professions Education

Many institutions are gradually adopting CBE, beginning with clearly defined outcomes competencies and programmatic assessment. Some programs have been successful in adding the other three components, although integrating all five core components can take time.

For a fully realized CBE system, health professions educators and administrators may define competencies across each stage of a health professional’s career, ensuring learners develop the right abilities at the right times. The goal is to create a healthcare workforce where graduates are equipped with the skills and knowledge necessary to meet the needs of their communities.

Key takeaways for clinician educators and leaders

Competency-Based Education represents a significant shift from traditional models, offering a framework that emphasizes mastery, accountability, and learner-centeredness. As you assess your own programs or those you may encounter, look for these five core components:

- Defined outcome competencies.

- A sequenced progression of learning.

- Tailored and mapped learning experiences.

- Competency-focused teaching.

- Programmatic assessment practices.

CBE isn’t a checklist but a design philosophy that prioritizes deliberate, outcomes-focused decisions to better prepare clinicians for the complexities of real-world practice. As CBE continues to grow in popularity, understanding these principles can help you design, evaluate, and refine programs that truly meet the standards of competency-based education.

Related articles and resources

- WHO (World Health Organization) has published the document “Competency-based curriculum development in medical education: an introduction”. This is the document Jason the document that Jason believes forms the basis of the modern definition in medicine, CBME.

- Van Melle, E., Frank, J. R., Holmboe, E. S., Dagnone, D., Stockley, D., & Sherbino, J. (2019). “A Core Components Framework for Evaluating Implementation of Competency-Based Medical Education Programs”. Academic Medicine, 94(7), 1002–1009.

- MedEd Studio: Jason Frank – Time and competency (ki.se)

About this article

This article is based on insights shared in the Papers Podcast Episode 72. Chat GPT has helped us to make content from the episode. Text is human-certified before published.

Reader response on the episode

We got this email from Dr Derek Louey from Flinders University in Australia with some comments on the last episode. Thank you, Derek, for your thoughts and invites to a deepening discussion on the subject. /Papers Podcast team.

“Dear Jason,

Thank you for Episode #72 of the Papers podcast, which offered an insightful summary of the core principles of competency-based education (CBE). Condensing the complexity of this concept into a 20-minute discussion is undoubtedly a formidable task. CBE appears to be aimed at achieving two conceptually distinct outcomes: ensuring minimal vocational competence and preparing learners to navigate the complexities of future clinical practice. However, the Van Melle framework seems insufficient in bridging these goals, particularly in the context of the intricate and dynamic environments of healthcare education and practice.

The podcast begins by outlining the value proposition of CBE as a means to reduce variation in graduate outcomes, ostensibly to mitigate patient harm. Yet, variation is intrinsic to both educational processes and clinical practice. It is an inherent aspect of the individualized and often unpredictable nature of learning. Moreover, variation is essential for the diverse services healthcare requires and is unavoidable in differing practice and geographical contexts. Critics of CBE might contend that minimizing variation can inadvertently stifle the pursuit of excellence. Apart from the most glaring examples of incompetence, CBE lacks clarity on when variation should be considered acceptable or even desirable.

Competency frameworks typically emphasize generic competencies applicable across contexts. (Hautz, Hautz, Feufel, & Spies, 2015). In contrast, the use of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) operationalises competence as the ability to address problems likely encountered in practice, such as diagnostic, management, adherence, or care coordination challenges. (ten Cate, Chen, Hoff, Peters, & Bok, 2015). Integrating these perspectives, competence might be defined as the capacity to apply knowledge, skills, and behaviours to context-specific problems within broadly defined domains. However, traits like professionalism are highly contextualized (Hodges, Paul, Ginsburg, & the Ottawa Consensus Group, 2019) and problem-solving abilities are similarly context-dependent.(Watsjold, Ilgen, & Regehr, 2022). Additionally, evidence suggests that the transfer of problem-solving skills to unfamiliar contexts is not straightforward.(Eva, Neville, & Norman, 1998). CBE does not explicitly address how learners will generalise knowledge and skills from their training environments to their future practice settings.

One of the initial challenges in implementing CBE is the criterion set forth by Van Melle. (Van Melle et al., 2019) which mandates pre-defined minimum outcome competencies. This raises critical questions: Are there core problems or skills that any competent clinician should independently address regardless of context? While it could be argued that a medical graduate should at least recognise a serious issue, even if unable to manage it, a clinician’s role cannot merely be one of recognizing and referring. Effective practice demands decisions about which problems must be independently addressed, yet the requisite knowledge and skills vary widely across healthcare settings. For instance, expectations at a quaternary referral centre differ significantly from those at a low-resource rural site where clinical acumen and resourcefulness are paramount. How should we define minimum competency in a way that accommodates these contextual differences? Moreover, how do we discern what knowledge is critical at present versus what can be learned later?

Graduates inevitably practice in a variety of contexts, requiring them to adapt and expand their knowledge and skills.(Matsuyama, Nakaya, Okazaki, Leppink, & van der Vleuten, 2018). Attributes such as self-awareness, self-efficacy, and self-regulation are integral to professionalism. There is increasing interest in fostering these adaptive skills in learners.(W. B. Cutrer et al., 2017; Mylopoulos, Brydges, Woods, Manzone, & Schwartz, 2016) The ability to navigate new challenges is a hallmark of expertise, (Cupido et al., 2022) and although this is indirectly addressed in competency frameworks under terms like “scholar” or “lifelong learner,” these concepts are often interpreted broadly. Competence in scholarship encompasses discovery, synthesis, application, and teaching,(Glassick, 2000), yet CBE does not explicitly articulate how learning activities translate to future uncharted challenges (William B. Cutrer et al., 2018; Mylopoulos, Kulasegaram, & Woods, 2018). There is a need for assessment systems that ensure the transferability of knowledge and skills developed during training.

Clinicians will inevitably encounter novel or complex problems. It is unrealistic to expect competence in all domains. More concerning is when unfamiliar problems are mistaken for familiar ones, leading to a knowledge-insight gap characterized by overconfidence and unrecognized incompetence. How does CBE prepare learners to recognize and navigate their limitations, balancing autonomy and resourcefulness with appropriate prudence? Ensuring learners are competent in known EPAs does not guarantee they will avoid misapplying familiar strategies to novel challenges. CBE must address how to teach learners to identify boundaries of competence and exercise discernment in clinical decision-making.

Mitigating these concerns is the knowledge that healthcare often operates within collaborative networks. Effective clinicians should manage routine problems independently while knowing when to seek assistance for more complex cases. Perhaps a minimally competent clinician is not one who can solve every problem but rather one who knows how to share responsibility effectively. The concept of collaborative, team-based competence is gaining recognition (Lingard, 2018). However, while individual competence may emerge from interactions within complex healthcare systems (Hodson, 2020), shared responsibility can also lead to diffusion of accountability (Simms & Nichols, 2014). Establishing a clear professional identity becomes challenging when it is influenced by surrounding team dynamics. The question of defining minimal individual competence remains pressing.

Identifying, teaching, and assessing discrete competencies is elusive and lacks transparency (Lurie, Mooney, & Lyness, 2009). The drive to reduce variation in outcomes must acknowledge the inevitability of contextual and practice-based differences. Whether conceptualising competence as a set of abstract traits or a prescriptive list of professional activities, the ecological complexity of healthcare complicates the establishment of universal standards. This complexity also poses communication challenges for faculty operating in varied settings.

The aspirations of CBE are laudable yet complex. Conceptualized as a multifaceted intervention, CBE encompasses numerous principles, philosophies, and implementation strategies(Cianciolo & Regehr, 2019). It seeks to reduce variation in outcomes but must contend with the inherent variability of learning environments. Not all variation is necessarily detrimental, and reconciling the image of a minimally competent, generic clinician with one who is prepared for the unpredictability of future practice remains a formidable challenge.

Kind regards,

Dr. Derek Louey

A peripatetic Australian Emergency Physician”

0 comments