#69 – Three Years to MD: Does It Measure Up?

Episode host: Jonathan Sherbino.

In this episode, we’re diving into the age-old question: is a three-year medical school program just as good as the traditional four-year track? The researchers compared the residency performance of graduates from both programs and found no significant differences, suggesting that you might not need that extra year after all—unless you’re really keen on more electives!

Episode 69 transcript. Enjoy PapersPodcast as a versatile learning resource the way you prefer- read, translate, and explore!

Episode article

Santen, S. A., Yingling, S., Hogan, S. O., Vitto, C. M., Traba, C. M., Strano-Paul, L., Robinson, A. N., Reboli, A. C., Leong, S. L., Jones, B. G., Gonzalez-Flores, A., Grinnell, M. E., Dodson, L. G., Coe, C. L., Cangiarella, J., Bruce, E. L., Richardson, J., Hunsaker, M. L., Holmboe, E. S., & Park, Y. S. (2023). “Are They Prepared? Comparing Intern Milestone Performance of Accelerated 3-Year and 4-Year Medical Graduates” (Academic Medecine). 2023 Oct 16:10-97.

Episode notes

Here are the notes by Jonathan Sherbino.

Background to why I picked this paper

In this week’s episode, we tackle a question that many medical school applicants and graduates have faced: How long should medical training be? It’s a decision I encountered many years ago, reminiscent of the scrolling introduction to Star Wars: “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, I went to medical school.”

As of late 2024, only about 10% of Canadian medical schools offer a three-year curriculum, compared to the more traditional four-year track. But why four years? This structure dates back to the Flexner Report for the Carnegie Foundation, which reshaped North American medical education over a century ago. But in today’s era of competency-based education, where undergraduate medical education is evolving rapidly, we must ask: is there something special about the four-year format? Or could it be three years? Six years, as in some European programs?

Proponents of the three-year track argue for reduced costs—three years of tuition is typically cheaper than four—and a faster entry into the workforce. On the other hand, advocates for the four-year curriculum highlight its flexibility, the opportunity for electives, and the chance for students to generate income while studying. From a non-competency-based perspective, a longer duration may also allow for a deeper, more comprehensive learning experience.

In the end, I chose the four-year program, reasoning (perhaps naively) that it would provide a superior education.

In today’s episode, we’ll weigh the evidence. In the blue corner, we have the traditional, battle-hardened four-year curriculum—a conservative, heavyweight contender that’s reigned supreme for over a century. And in the red corner, we have the up-and-coming three-year curriculum, nimble, cost-efficient, and eager to challenge the status quo. Let’s dive into the data and see what the evidence says.

Purpose of this paper

From the authors:

“This study aims to determine whether 3-year graduates and 4-year graduates have comparable residency performance outcomes”

Methods used

This was a non-inferiority study design with matched data:

- 182 3YP students.

- 2717 4YP students who graduated from hybrid medical schools with both 3 and 4 YPs.

2021 – 2022 US ACGME data from:

- EM, FM, IM, GS, Psych, Peds (6 largest specialties).

- 16 medical schools w hybrid programs of both 3 and 4YPs.

Milestone data at 6 months and one year

- scored 0 – 5 (with 0.5 increments) with target of >=4 by residency graduation.

- Domains of systems-based practice, practice-based learning and improvement, professionalism, and interpersonal and communication skills are harmonized across all specialties. All specialties compared.

- Patient care and medical knowledge are unique to specialty. IM and FM compared.

+/-0.50 point difference as non-inferiority ~=ES of 0.6.

Sample size sensitive to ES = 0.2.

Descriptive statistics and a cross-classified random-effects regression was conducted.

Results/Findings

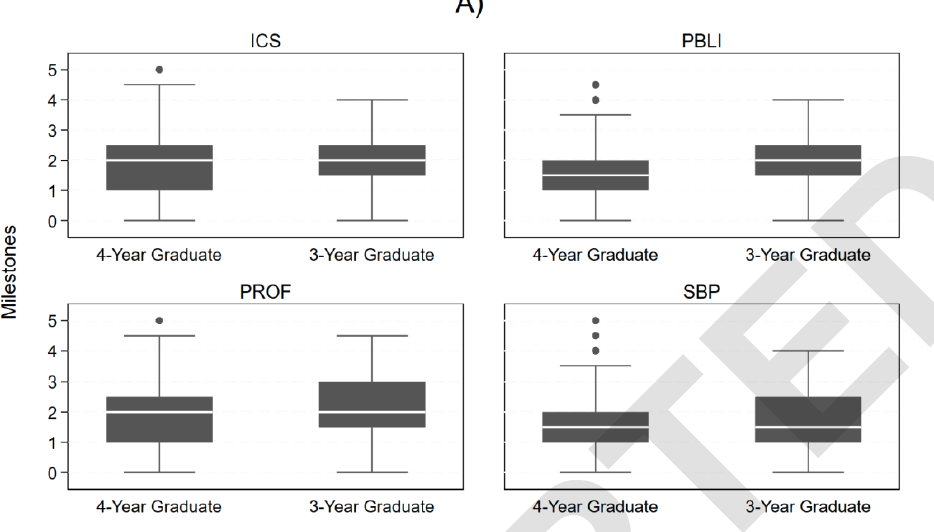

Mean aggregate ratings at six months (1.95 [0.8SD] 3YP v 1.83 [0.84 SD] 4YP) and one year (2.33 [0.78] v. 2.22 [0.84]) show no differences.

Regression analysis showed no difference within any domain.

5% of 3YP participants had at least one milestone rating of zero (not ready for supervised practice), compared to 2% of 4YP participants at one year of residency training. The finding was not significant.

There was no significant difference between subgroup analyses of IM and FM residents, including evaluation of patient care and medical knowledge.

Conclusions

From the authors:

“Length of medical school training (3 vs 4 years) is not associated with residency performance as assessed by the [ACGME Milestones] in the first year of training, for the Harmonized [scores] across specialties, and in internal medicine and family medicine.”

Paperclips

This study is a great example of “big data” answering questions previously not possible. The development of shared and aggregated data sources is essential to challenging system-wide conventions of HPE.

T

Acknowledgment

This transcript was generated using machine transcription technology, followed by manual editing for accuracy and clarity. While we strive for precision, there may be minor discrepancies between the spoken content and the text. We appreciate your understanding and encourage you to refer to the original podcast for the most accurate context.

-

What factors have contributed to the persistence of the four-year medical school model in Canada, and how might alternative formats like three-year or competency-based programs better align with evolving educational and healthcare needs?

Regard IT Telkom

1 comments