#76 – A review on modern teaching and learning techniques in medical education

Episode Host: Jonathan Sherbino.

Are your students truly engaged?

In this episode, the hosts dive into a micro-monograph that shakes up stale teaching techniques by showcasing fresh, student-centered methods that go way beyond the classic lecture snooze-fest. With plenty of laughs and a dash of nostalgia, they share their own teaching experiments, swapping old-school habits for bold, adaptable approaches to keep both educators and students on their toes in today’s fast-evolving medical world.

Key takeaways of this weeks episode

- Modern methods like case-based learning, simulation, and flipped classrooms are reshaping medical education.

- These methods foster critical thinking, collaboration, and hands-on experience but come with challenges like resource demands and group dynamics.

- Flexible, student-centered approaches and tools like VR/AR and gamification enhance engagement and effectiveness.

- Educators should reassess outdated habits and adopt evidence-based techniques.

Where to listen and find transcripts

Listen to PapersPodcast at your preferred podcast player:

Apple, Spotify, Spreaker, YouTube

There are transcripts! Enjoy PapersPodcast as a versatile learning resource the way you prefer- read, translate, and explore. Episode 76 transcript.

Episode article

Karkera S, Devendra N, Lakhani B, Manahan K, Geisler J. “A review on modern teaching and learning techniques in medical education”. EIKI Journal of Effective Teaching Methods. 2024 Jan 26;2(1).

Episode notes

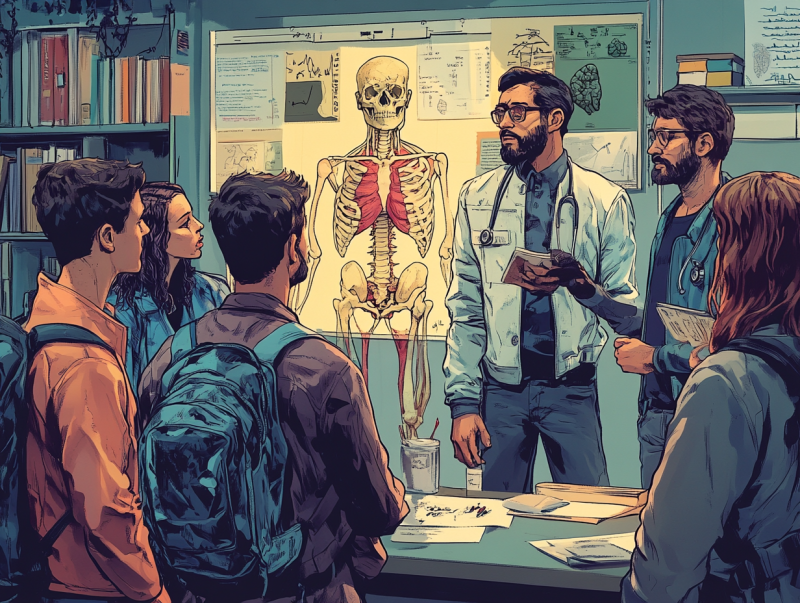

Background (Jonathan)

I’ve been reflecting this week on the variety of literature we discuss on the pod. If I were to conduct an ethno–subject–quasi-experimental–thematic–auto–crossover–nonequivalent–thematic analysis (insert Varpio’s head exploding), here are some areas we dive into. No surprise, I’m passionate about tech and experiments with stats, even though neither comes naturally to me. We frequently talk about professional identity—thanks to Linda. And Laura, you keep us grounded (see what I did there?) And Jason,… I’m overwhelmed by the temptation for a cheap joke… your interest lies in policy and system design.

As I look back, I realize what sparked my journey into health professions education: a desire to become a better teacher. My graduate thesis, a workshop-based innovative curriculum design, reflects that commitment—though calling it “innovative” might be stretching it a bit. So, this week is a return to the “essentials” – the literature to support teaching and various instructional methods. To centre our conversation, I’m digging into a journal I’ve never explored before: the Journal of Effective Teaching Methods (JETM – love the abbreviation) It’s published by the European Institute of Knowledge and Innovation, which markets itself as a scientist-founded, independent academic organization focused on promoting professional development and continuing education.

Before diving into the article, it’s crucial to acknowledge the foundational literature that shapes our roles as educators. Just because we’ve been students for so long doesn’t mean the teaching habits we’ve adopted over time are optimal or even effective. Survivorship bias might suggest that some practices have lasted because they work, but that shouldn’t stop us from reassessing our instructional methods. It’s time to explore new approaches, discard outdated practices, and gain a deeper understanding of why certain techniques are effective.

So, let’s delve into this study by Karkera and colleagues from Trinity Medical Sciences University in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in the Caribbean.

/Jonathan

Purpose of the article

From the authors: “to discuss and analyze different teaching-learning methods in contemporary medical education.”

What becomes apparent – essentially in the discussion – is that this is a micro-monograph of alternatives to a large group didactic (i.e., lecture) format.

Methods

This is a synthesis of pre-defined instructional methods. I prefer to categorize this as a “narrative” review. See the Litr-ex (Literature Reviews Explained) site for more details on narrative review.

A systematic search of Pubmed (FYI: the authors separately searched Medline, which is included in Pubmed) and the grey literature via Research Gate and Google Scholar using free text search but not MeSH headings.

English articles from 2000-2023 were included if they were peer-reviewed, open-access, and had a sample of>150 participants.

Results/Findings

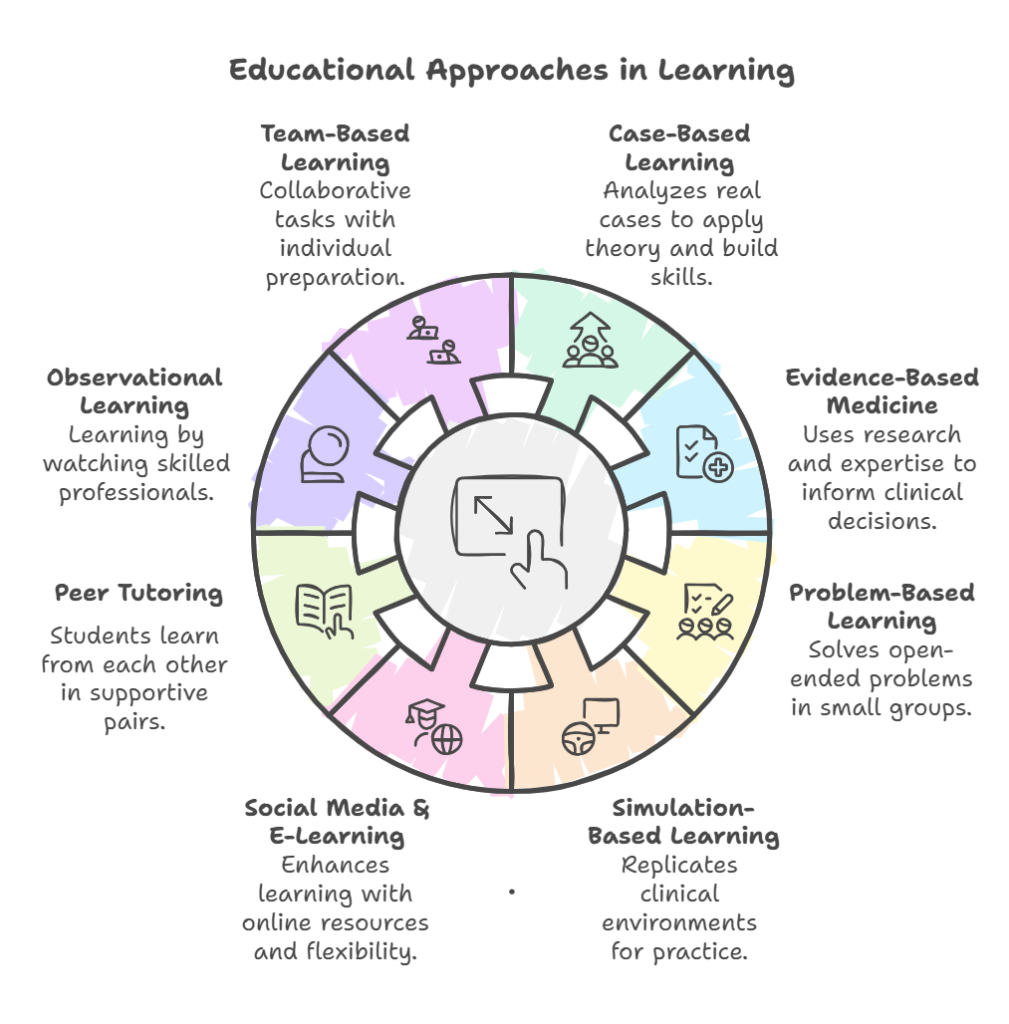

From 25 articles, 10 articles were included in the synthesis. 11 teaching methods are described. Here follows a summary if the methods.

1. Case-Based Learning

- Instructional Method: Involves analyzing real-life or hypothetical cases to apply theoretical knowledge to practical problems. Typically done in groups, where students discuss and dissect complex cases to reach conclusions or solutions, building analytical and decision-making skills in a collaborative setting.

- Opportunity: Encourages critical thinking and practical application. Develops teamwork and communication skills. Improves retention by linking theory to real-world scenarios.

- Challenge: Requires well-structured cases that align with learning goals. Can be time-consuming. Effective group participation can be challenging.

2. Evidence-Based Medicine

- Instructional Method: Emphasizes using the best available, current, and relevant research to make clinical decisions. Integrates research evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values, ensuring that medical practice is grounded in well-supported evidence.

- Opportunity: Enhances patient care with data-backed decisions. Reduces errors and promotes best practices. Supports efficient, cost-effective treatment strategies.

- Challenge: Requires familiarity with research databases and analytical skills. Time-intensive to gather, interpret, and apply evidence. Needs understanding of biostatistics.

3. Problem-Based Learning

- Instructional Method: Focuses on student-led inquiry where learners work in small groups to solve open-ended problems, typically with minimal guidance. The problem serves as a trigger for learning new information and fosters self-directed learning.

- Opportunity: Develops critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Encourages teamwork and collaborative learning. Promotes long-term retention through active engagement.

- Challenge: Demands active student involvement, which not all learners may embrace. Requires skilled facilitators. Group dynamics can affect learning outcomes.

4. Simulation-Based Learning

- Instructional Method: Uses high-fidelity simulations, mannequins, or virtual simulations to replicate clinical settings, allowing students to practice skills in a controlled environment without risking patient safety.

- Opportunity: Provides hands-on practice without patient risk. Allows repeated practice to master skills. Builds confidence for real-life scenarios. Encourages teamwork and communication.

- Challenge: High setup costs for equipment and software. Needs space and scheduling for simulation labs. Instructors require specialized training to facilitate effectively.

5. Social Media & E-Learning

- Instructional Method: Integrates online resources, video lectures, and social media for learning, allowing flexibility and access to a wide range of multimedia materials. Often used for remote or asynchronous learning, enhancing flexibility for students and teachers.

- Opportunity: Flexible, accessible, and asynchronous. Offers diverse resources and platforms for varied learning styles. Supports continuous learning with global access.

- Challenge: Limited clinical skill development compared to in-person learning. Potential for technical issues. May result in reduced engagement without structured guidance.

6. Peer Tutoring

- Instructional Method: A method where students learn from each other, typically pairing a more knowledgeable student with a peer who needs support. Encourages cooperative learning and fosters supportive relationships among students.

- Opportunity: Enhances comprehension through collaborative learning. Builds student confidence and academic motivation. Promotes interpersonal skills and peer support.

- Challenge: Requires careful planning to match tutors with peers. Needs ongoing supervision and feedback to be effective.

7. Observational Learning

- Instructional Method: Involves learning by observing skilled professionals or peers performing procedures. Often used for motor skills and procedural tasks, allowing students to visualize and then replicate skills.

- Opportunity: Easy to implement with minimal resources. Useful for understanding complex procedures through demonstration. Applicable to a variety of instructional settings.

- Challenge: Passive learning approach may not engage all students. Time-consuming and can lead to disinterest. Limited retention without hands-on practice.

8. Team-Based Learning

- Instructional Method: Structured learning that emphasizes team collaboration and problem-solving. Students prepare individually, then work in teams to complete group tasks, often including immediate feedback from instructors.

- Opportunity: Promotes teamwork, communication, and accountability. Increases engagement through peer interaction. Provides a real-world collaborative experience.

- Challenge: Requires effective management of group dynamics. Some students may dominate, while others remain passive. Resistance from students unfamiliar with team assessments.

9. Flipped Classroom

- Instructional Method: Inverts the traditional classroom structure by having students study lecture materials at home and engage in interactive activities in class, promoting active learning during class time.

- Opportunity: Facilitates active learning and class discussions. Encourages self-paced pre-class preparation. Allows teachers to focus on interactive, high-level activities in class.

- Challenge: High preparation time and resource demands for instructors. Relies heavily on students completing pre-class work. Limited immediate feedback during individual study.

10. VR/AR Learning

- Instructional Method: Utilizes virtual and augmented reality to create immersive, interactive learning environments. Especially useful for complex, hands-on tasks and 3D visualizations of anatomical structures or surgical procedures.

- Opportunity: Provides an immersive, hands-on experience. Useful for practicing complex tasks without risk. Enhances understanding of 3D structures and spatial relationships.

- Challenge: Expensive to implement and maintain. Requires technical expertise and setup time. Limited accessibility for students without necessary devices.

11. Gamification

- Instructional Method: Integrates game elements (e.g., points, rewards, levels) into learning activities to increase motivation and engagement. Often includes competition and progress tracking, making learning more interactive and enjoyable.

- Opportunity: Increases motivation, engagement, and active participation. Encourages retention through interactive tasks. Allows creative exploration of complex topics.

- Challenge: May not be effective for long-term retention. High initial implementation cost. Limited mainstream acceptance in medical education.

Educational Approaches in Learning

Conclusions

From the authors:

“Flexibility is key in medical education, and our curriculum should be adaptable enough to accommodate and incorporate multidisciplinary teaching models effectively and contextually… the conclusion advocates for an adaptable and student-centered approach in medical education, recognizing the evolving nature of the learning process and the unique needs of individual learners.”

0 comments