#17 Context is Everything: The Challenges of PBL Around the World

Episode Host: Jonathan Sherbino

Enjoy listening to us at your preferred podcast player.

Episode article:

Chan, S. C. C., Gondhalekar, A. R., Choa, G., & Rashid, M. A. (2022). Adoption of Problem-Based Learning in Medical Schools in Non-Western Countries: A Systematic Review. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 0(0), 1–12.

This episode explores the challenges of transplanting PBL outside of a Western culture. The authors use meta-ethnography to synthesize the literature.

Background

McMaster Medical School, where I am on faculty, recently celebrated its 50th anniversary. That milestone is notable as McMaster claims to have invented problem-based learning (PBL). PBLs origins are slightly unclear; in fact it may be a derivation of the case method developed by the Harvard business school. And certainly, Maastricht University deserves considerable recognition in advancing the design and supporting psychology of learning of PBL.

But first, how to define PBL? As per usual, definitions in HPE are missing for PBL. When you look at the literature, tehre is inconsistency as to what constitutes this educational intervention. For our purposes, (and at McMaster) there are 4 elements to consider:

- Organization of the curriculum around a clinical (i.e., patient) case (i.e., problem).

- Self-directed learning

- Small group discussion

- Self and peer assessment.

While I am familiar with the impact of PBL locally (and nationally within Canada), the broader global influence of PBL is unknown to me. Enter Chan et al. These authors tackle the general problem of the globalization of medical education, where a “lift and shift” of an educational innovation into a different culture and context is not considered, nor accommodated.

Purpose

From the authors: “What are students’ and teachers’ experiences of PBL approaches in undergraduate medical programs in non-Western countries?”

Methods

A systematic literature search of PsychINFO, MEDLINE and ERIC was conducted. A hand search of the references of identified manuscripts was also conducted. Restrictions included English language publications and medical students. Duplicate screening for inclusion was conducted on 10% of the titles.

Included articles were scored using the critical appraisal skills program (CASP) checklist.

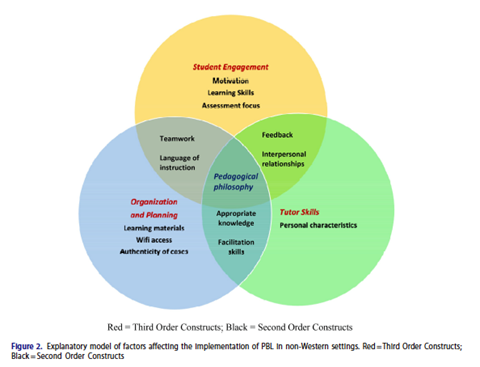

The data was synthesized using a meta-ethnographic approach. Meta-ethnography identifies key concepts (themes). Key concepts are supported by first order constructs that are the “raw data” from a study. Second order constructs are the authors interpretations of the primary data. Third order constructs form via the determination of the relationship of key concepts and the supporting first and second order constructs. This occurs when concepts are juxtaposed and considered across studies.

The authors acknowledge they are based in a single Western country (United Kingdom), but they have personal and educational experience in southeast Asia.

Results/Findings

1,084 manuscripts were identified; 41 articles were included in the synthesis. All articles met the CASP quality benchmark. The studies included data from 5,100 students, 360 facilitators in 18 different countries from Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 6 of the 41 studies were classified as a “key paper.”

PBL, as designed in the West, suggests a continuously critical mind to facilitate discussion and debate. However, non-Western students may have values that do not align with PBL philosophies, creating barriers to engagement.

Conclusions

From the authors:

“This study highlights how PBL implementation in a non-Western setting requires institutions to make significant modifications to ensure students engage with PBL methods whilst respecting cultural variations and interests. Medical education leaders and policymakers in non-Western countries should be cognizant of the fact that PBL does not “lift and shift” easily outside of the Western context in which it was developed, and should adjust their adoption strategies accordingly.”

References

Literature Reviews Explained (LITR-EX) – Evidence-Informed Practical Guides to Conducting Literature Reviews in (but not limited to) Health Professions Education.

If you want to learn a little more about meta-ethnography, check out this primer with a worked example: Sattar, R., Lawton, R., Panagioti, M., & Johnson, J. (2021). Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 50.

0 comments